Drawing-objects

- You draw?

- Yes, sometimes.

- You draw what?

- I catch “drawing”.

- You mean, you don’t draw something, then!

- No, I want « drawing », like a thing that I could hold in my hand: seize “drawing”.

- You mean that you’re not interested in what the drawing draws, but in the drawing itself as if it were a thing?

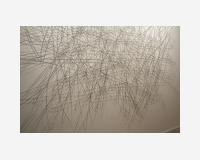

- A body; I catch this body of the drawing thrown after itself which is the line. From the space of the page I use a sharp knife to very carefully extract the trace left by the pencil, by a marker or by ink – no matter what material – of what “drawing” leaves there, under my eyes. I incarnate it.

- When you’re drawing you are running after something that you want to catch?

- Yes. When I’m drawing I lay the preliminary line of what will be a foreign body fallen into real space, later on, once I’ve cut it out.

- “Fallen”?

- Yes, fallen. When we actually grasp the image it suddenly appears in its bodily materiality: it’s a skin, soft, it can’t hold together…it falls. To touch the image – and that’s why it needs a distance: the “Noli me tangere” of the focal distance – it is to put it outside of itself.

- And your work opens out at the crossroads of this touching and its consequences?

- Yes, you got it! At the junction between the space of the image and the space of the body, at the turning-point or the passage where real and imaginary are a threshold for each other. The drawing is like the incarnation before my eyes of this limit: where your brush touches the medium of the image, what the brush leaves as a clue to the resistance of the material thing which is the image, cannot be resolved in it. To draw is to touch; it is the journey of that touch left before my eyes, left to the possible decoding by the one who will in turn look at it. Painting means to spread a trace up to the point where it forgets itself completely. And this trace cannot fail to be, at the outset of the painting, the trace of the very materiality of the object which is the painting, and which the painting, in its essence,endeavorsto veil and to disguise. As for the drawing, it incessantly brings back to the surface the trace of that first material resistance of the medium of the image when we touch it in order to make the image. There is no way of getting round this. Maybe this is what the one who draws takes on board: this stroke, that mark that the painter (or any other image maker come to that) comes up against at a certain moment – of too much of the final picture in the image. This first line when the pencil meets the sheet of paper which is also the first mark of the intention of the one who, pencil in hand, approaches the image. It is, shall we say, the navel of the image.

- And you, yourself, struggle to grasp this first line as if it were an object ?

- Yes. The painter spreads the material of this line until it disappears and the image appears. Whereas I seek to extract in the image the clue of this impact from which the image comes. I seek the point where the image has in some way been touched before it was this image – touched so that it should be an image. Yes, images are made. They do not come from nowhere. There is firstly a time when the image is not there and this time is the feverish waiting for the image. This expectation is represented by the first line of the drawing which marks the image or which marks the place where the image will come before it does so. This line is in a wandering pursuit for the image. The line of the drawing does not yet know which shape it will suddenly enclose. When it runs, it is this expectation, this tension towards the image…the desire for the image.

- The drawing is therefore the desire for the image?

- I seek to embody something of the thickness that separates the one approaching the image from the image itself.

- The other day you referred to the writer PascalQuignardwhen speaking of this question of the desire for the image.

- The image is a moment that we anticipate feverishly. The image maker is surely a lover but a lover whose love has taught him about the danger of his objective. He desires what fascinates him. His effort necessarily involves not letting himself be completely swallowed up by that to which he is heading. The painter, in making the moment of the image his moment, takes on board the question of the time which separates him from that moment. And this time is a space, or a thickness to go through, a distance that is never completely finished with. This distance is his vital space. This distance is the stroke of the drawing. It represents the limit that separates the one who draws from the image he is approaching by drawing. The marks he leaves while drawing, between “what he draws” and himself, are the line that is the guard rail that prevents him from falling into “what he draws”.

- What about Quignard?

- He brought up the etymology of the word “desire”: “de-siderare”. Desire is to go beyond that which previously held us in a stillness in ‘stills’ where the image captivates our eyes. I always come back to what, for me, waking up begins with. “I draw a line”: it is the line of the eyelids when we close our eyes. The first line of the drawing is that chosen blindness which means we see less what is in front of us and holds us still, in order to want it. This line I draw is to unstop myself. I am asleep in my looking at a first image, and this will be substituted by one that is missing, one that appeals beyond each one, one that is not there and that is represented by the one I have in front of me – so I go beyond the latter one and run after the former; so that I can run after….

- And this statement sails joyfully on your drawing ?

- Yes, the spatialtheaterof this passion. Image is a strategy of approach. And it necessarily has to do with “blind”.

- With your drawings, of which you say that they are not so much the drawings of something but the thing of the drawing, you introduce in the visible a “less”, a “see

less”. You like to say that for you this is salutary.

- That is the condition. If you like, I bring us back into the visible with our eyes closed.

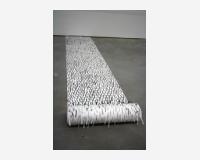

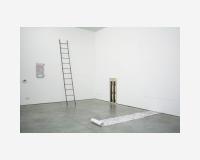

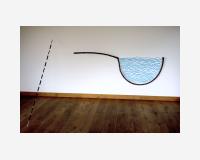

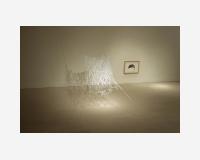

- And actually your drawings or your lines are no longer drawings because you cut them out and you set them as traps in space, vision traps and even real traps in that the onlooker who maybe gets his feet caught in them will destroy them by being trapped in them…

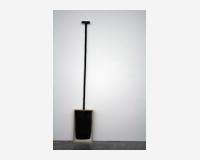

- Yes ! I callthem« incarnations ». These pieces that are images out of themselves, or taken out of themselves, cannot hold up. As soon as we touch an image it can no longer hold up. So how can we give them back body? It is paradoxical because a little earlier I said that they were bodies – fallen bodies. Well this is where a question that I hold dear takes on body: a body does not hold up unless it ‘makes image’ before us. I tangibly encountered this obvious fact over the years I spent in contact with psychotic children and teenagers I was working with. If we need, at a first stage, to undo the fascination that the image has on us, we then discover that it doesn’t work either without resorting to the image. The body needs an imaginary aura, the stuff of an image or a speech that will stage it so that it can stand like something other than an object fallen or depressed before us.

My objects, extracted from the image, these inarticulate bodies that I hold like the skin of the drawing at my finger tips, I must eventually give them back the aid of illusion that I worked against at first. We wouldn’t want to go too far we cannot do without it. a body must give at least a little of the illusion that it is there in order for it to be there before us. There is a minimum we need to believe in: I mean that we advance, we take on body, we become who we are, on condition that we project ourselves into the space, onto the stage of what we believe in.

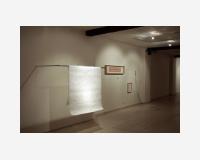

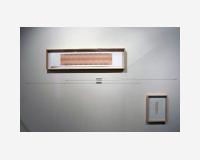

At a second stage I move on to giving back to these objects extracted from the image space the consistency of something that stands in front of us. I install them and they take on the name of “objects that are not objects because they are drawings, drawings which are not drawings because they are objects” there before our eyes, in the space where we ourselves move with our bodies. They are edges. They are the game of embodying the edge where real space and imaginary space connect and move about each other. They are a sort of interface, both a joining together and a separating between the two.

I also call them ambassadors, referring to the famous anamorphosis of Holbein. We see them standing in space like objects, before identifying them suddenly as the pictorial event of their lines on the surface of a sheet of paper (I use a synthetic paper reputed to be “tear-proof” so that it stays put). Then what happens? Have these objects that were taken out of the painting come to us bodily in order to change the nature of the space through which we move? Is it the painting that at once actually evolves in our space? Or is it us who from this moment on advance in the space of the painting?

...

Félicien Béni, extract from an interview with Benoît Félix, December 2010 Translation: Norman Taylor